The Color Chocolate History

The questions I have been investigating lately is when did, “chocolate” become a word to describe a color and what color was that, exactly? These questions are not as simple as they may seem; the answers have much to do with the cultural history of chocolate and how color gives flavor to our lives.

In the Central American homeland of chocolate, cacao-rich foods and drinks have been a part of life for thousands of years. Linguists debate about the origin of the word “cacao”, the tree seed from which chocolate is made, but it is clear that the word for cacao is very old indeed. The word ‘chocolate’ in Mexico and Central America, however, is a relative newcomer, a Nahua word, from the same language family as the Nahuatl the Aztecs spoke. In pre-Columbian writing, chocolate and cacao indicate substances, not colors.

In the sixteenth century, chocolate was widely known as a special drink from colonial Guatemala (that also included today’s El Salvador). European colonists consumed cacao-based beverages as early as the sixteenth century, but “chocolate” did not immediately become part of the vocabulary of other languages such as Spanish, English, or French when they started consuming cacao-laced foods and drinks. Chocolate was a substance so unusual that Europeans did not re-use a familiar word to describe it—they adopted the foreign Nahua name. So, when did this foreign substance infiltrate European ideas about color?

Chocolate as a Color

The idea of chocolate as a color shows the gaps we face among the documentary, visual, and material records. Chocolate came in many different forms and colors, so figuring out what tint people called “chocolate” says much about what the iconic feature of chocolate was. Early uses of the word “chocolate” as a color do not appear until the early eighteenth century, after Europeans had been consuming chocolate for some time. This new use of the word indicates a broad enough familiarity with the substance that it made sense, and it happened at about the time of an upswing in popularity of browns.[1]

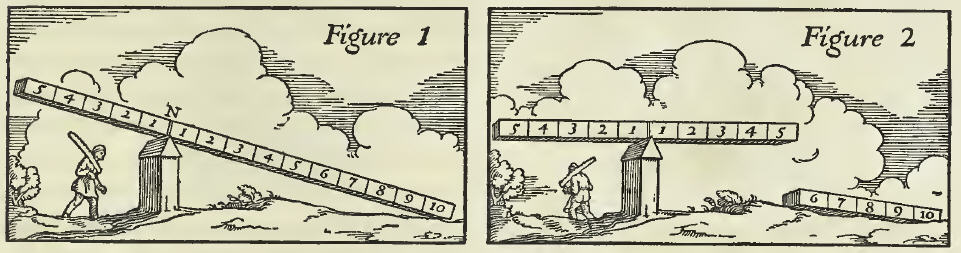

Figure 1. Color samples of browns, p. 74, in Werner’s nomenclature of colours : with additions, arranged so as to render it highly useful to the arts and sciences, particularly zoology, botany, chemistry, mineralogy, and morbid anatomy : annexed to which are examples selected from well-known objects in the animal, vegetable, and mineral kingdoms (1821), Werner, Abraham Gottlob; Syme, Patrick, editor; James Ballantyne and Co., printer, Edinburgh : Printed for William Blackwood, Edinburgh, and T. Cadell, Strand, London (https://archive.org/details/gri_c00033125012743312).

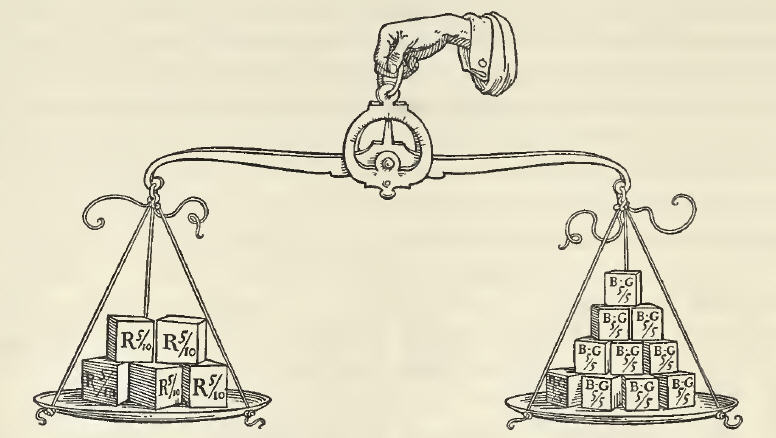

An early use of ‘chocolate’ as a color occurred in William Salmon’s 1734 Palladio Londinensis, Or the London Art of Building to describe a house paint color. A detailed 1692 color guide written in Dutch includes many shades of brown (Figure 1). Likewise, in the historic textiles and clothing in the collection of the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, browns are popular from about 1740-1760. Of all these browns, which one was “chocolate” brown? In the seventeenth and eighteenth century, chocolate was consumed as a frothy drink rather like today’s lattes, but it was also eaten as a paste and sold in tablets and bars. The lighter browns most closely match the foam of whipped chocolate, while darker browns best match the liquid from the drink or even solid chocolate.[2]

Figure 2., Folio 65r of Traité des couleurs servant à la peinture à l’eau, a manuscript from 1692, (http://www.e-corpus.org/notices/102464/gallery/773852)

One of the best clues about the hue of chocolate comes from the 1821 edition of Werner’s nomenclature of colours (Figure 2), which includes both a color description and sample. Curiously, “chocolate” describes a red, not a brown (Figure 3). Browns are named for other food terms, such as clove, broccoli, and chestnut. All of this highlights that ideas of color are very much rooted in personal experience. Choices in names evoke a whole slew of associations.

Figure 3. Color description of “Chocolate Red,” p.71 in Werner’s nomenclature of colours.

Determining the Colors of Chocolate

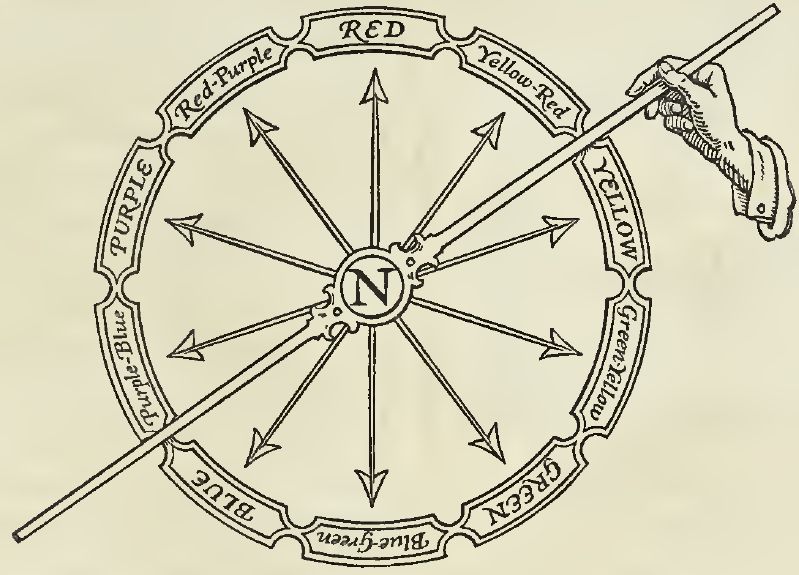

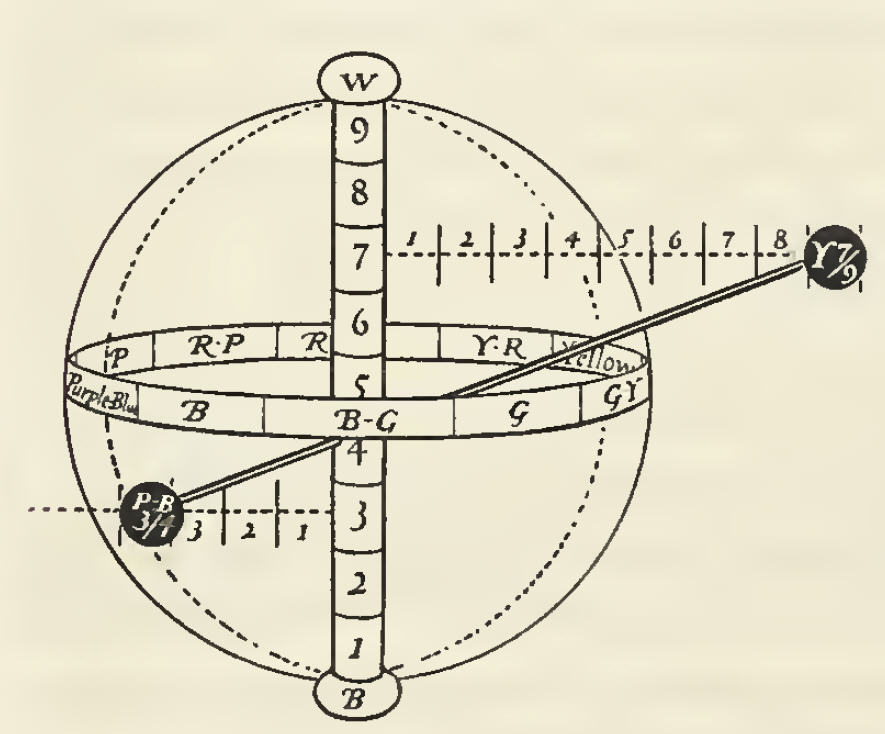

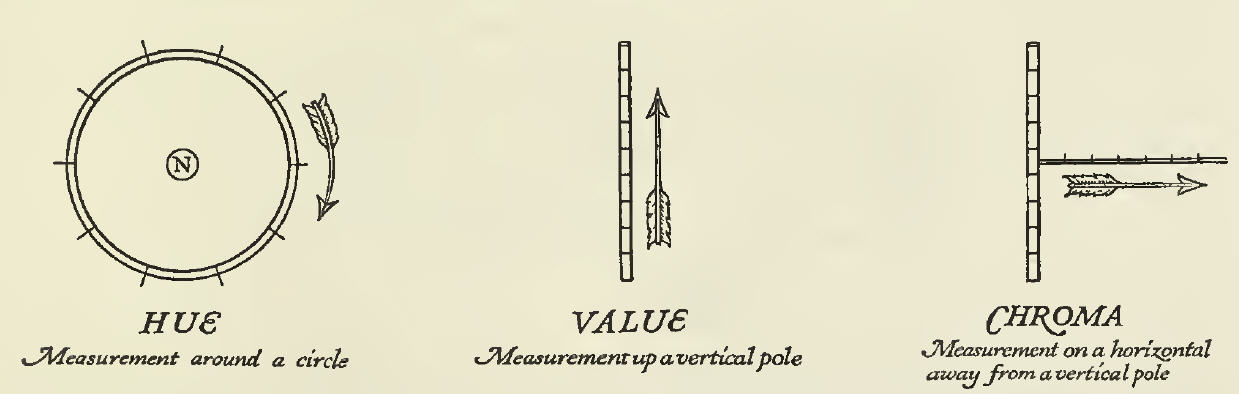

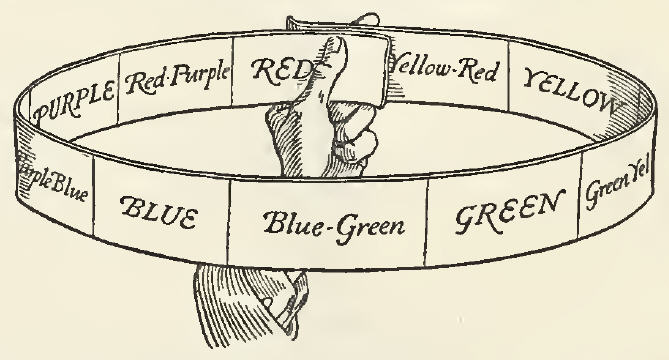

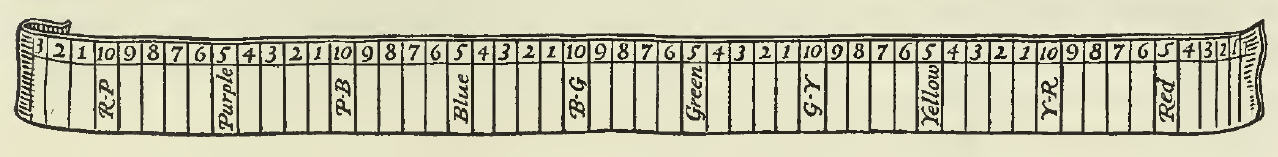

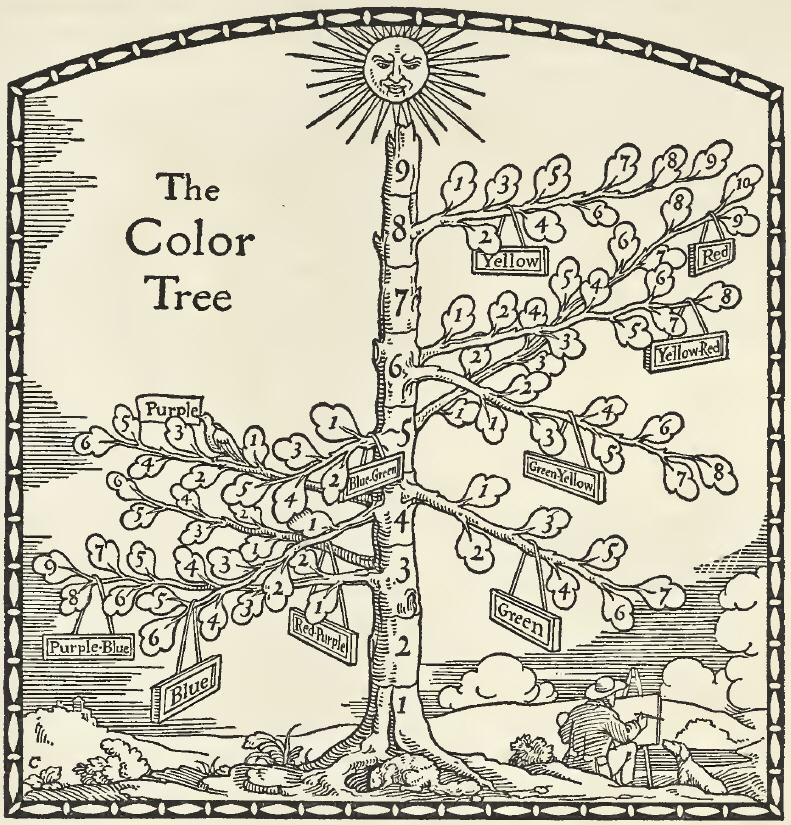

How then, can we pin down “chocolate brown” today? The Munsell color guide provides a kind of Rosetta Stone to translate historic uses of color names and examples into a standard color vocabulary of scales in hue and chroma. The Munsell system avoids references to plants, foods, or animals–quirky, experience-based terms–in favor of more widely applicable descriptions such as “strong” or “very dark.” While we do not find “chocolate” in the Munsell Color Guide, it offers a way to evaluate all the historical nuances of chocolate and personhood; we can see chocolate more clearly. Munsell is a tool of the present to understand color vocabulary of the past.

[1] See more about color and clothing here: http://kathrynsampeck.wordpress.com/2013/09/27/the-color-of-its-countries-chocolate-clothing-and-personhood-in-the-eighteenth-century/

[2] An earlier Munsell blog has excellent examples of chocolate colors: http://munsell.com/color-blog/chocolate-color-notation/

About the Author

Dr. Kathryn Sampeck is an Assistant Professor of Anthropology at Illinois State University. She earned her B.A. and M.A. from the University of Chicago and her Ph.D. from Tulane University. Her research focuses on the archaeology and ethnohistory of Spanish colonialism, Mesoamerican literacy and writing, and the social history of American commodities such as cacao. Sampeck has been awarded fellowships by the John Carter Brown Library and the John D. Rockefeller Library, Colonial Williamsburg as well as grants by the National Science Foundation, Wenner-Gren Foundation for Anthropological Research, Social Science Research Council, Fulbright program, and Cherokee Preservation Foundation. Her publications include articles in the International Journal of Historical Archaeology, Mesoamérica, Ancient Mesoamerica, and La Universidad, as well as forthcoming works in American Antiquity, Historical Archaeology, and Ethnohistory. She tweets and posts about colonial life, Latin America, archaeology, and chocolate regularly—follow her on Twitter, Instagram and her blogs on http://kathrynsampeck.wordpress.com/ and http://colonialcherokeearchaeology.blogspot.com/ – See more at: http://munsell.com/color-blog/brown-soil-color-chart-archaeology/#sthash.0insfWdI.dpuf

Dr. Kathryn Sampeck is an Assistant Professor of Anthropology at Illinois State University. She earned her B.A. and M.A. from the University of Chicago and her Ph.D. from Tulane University. Her research focuses on the archaeology and ethnohistory of Spanish colonialism, Mesoamerican literacy and writing, and the social history of American commodities such as cacao. Sampeck has been awarded fellowships by the John Carter Brown Library and the John D. Rockefeller Library, Colonial Williamsburg as well as grants by the National Science Foundation, Wenner-Gren Foundation for Anthropological Research, Social Science Research Council, Fulbright program, and Cherokee Preservation Foundation. Her publications include articles in the International Journal of Historical Archaeology, Mesoamérica, Ancient Mesoamerica, and La Universidad, as well as forthcoming works in American Antiquity, Historical Archaeology, and Ethnohistory. She tweets and posts about colonial life, Latin America, archaeology, and chocolate regularly—follow her on Twitter, Instagram and her blogs on http://kathrynsampeck.wordpress.com/ and http://colonialcherokeearchaeology.blogspot.com/ – See more at: http://munsell.com/color-blog/brown-soil-color-chart-archaeology/#sthash.0insfWdI.dpuf

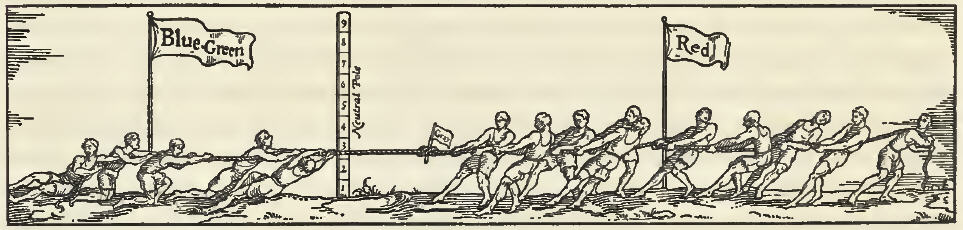

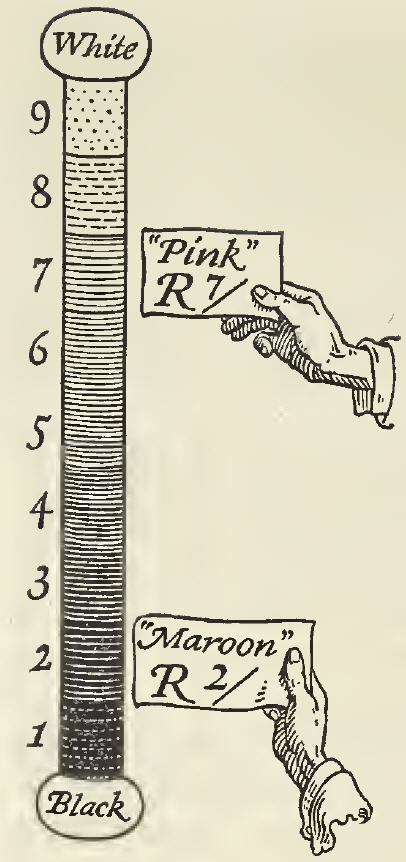

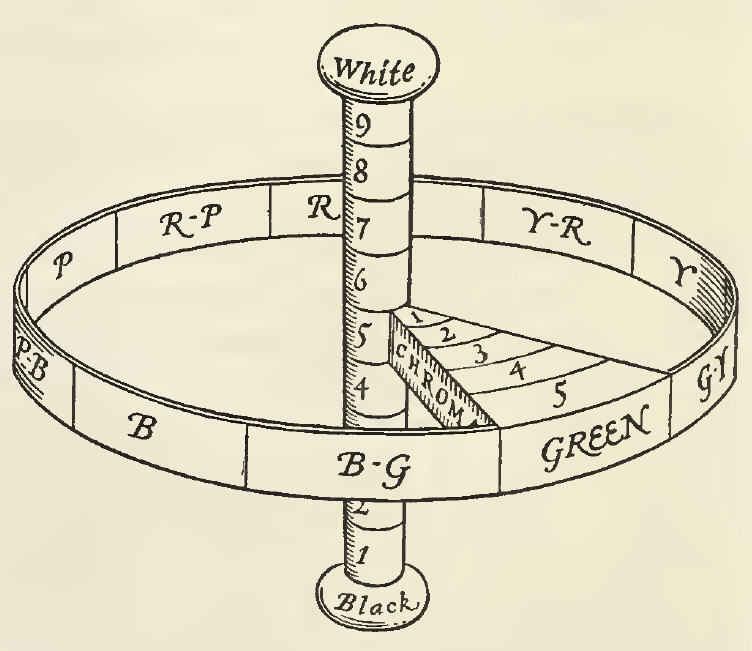

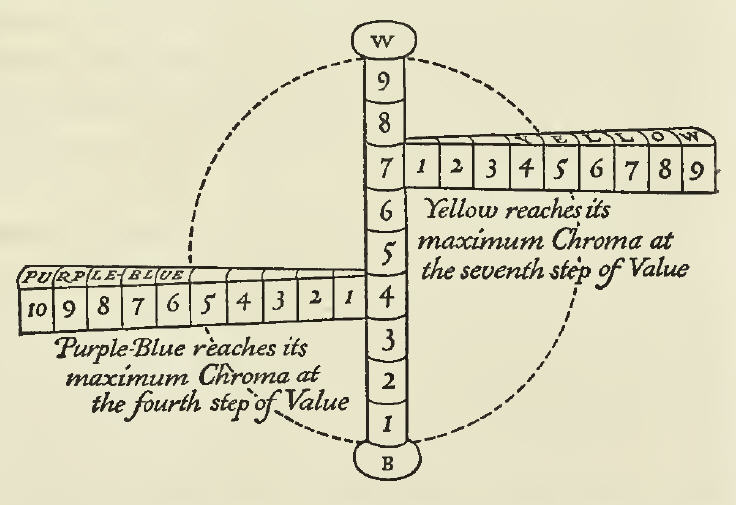

This is the second dimension and is possibly the simplest to understand. It is, according to Professor Munsell’s definition, “The quality by which we distinguish a light color from a dark one.” We noted that the first dimension did not tell us whether a color was light or dark. It told us, for example, that it was red and not green, but we know that there may be light red and dark red, and it is the function of this

This is the second dimension and is possibly the simplest to understand. It is, according to Professor Munsell’s definition, “The quality by which we distinguish a light color from a dark one.” We noted that the first dimension did not tell us whether a color was light or dark. It told us, for example, that it was red and not green, but we know that there may be light red and dark red, and it is the function of this

Aleksandar Macasev

Aleksandar Macasev

Mikael Vejdemo-Johansson is a mathematician, postdoctoral researcher, programmer, system administrator, photographer and amateur musician. He received an Fil.Mag. (M.Sc.) in Mathematics at Stockholm University in 2005 and doctorate from Friedrich-Schiller-Universität Jena, Germany, in 2008. Since then I have been at Stanford, the University of St Andrews, KTH and the Jozef Stefan Institute as a postdoctoral researcher.

Mikael Vejdemo-Johansson is a mathematician, postdoctoral researcher, programmer, system administrator, photographer and amateur musician. He received an Fil.Mag. (M.Sc.) in Mathematics at Stockholm University in 2005 and doctorate from Friedrich-Schiller-Universität Jena, Germany, in 2008. Since then I have been at Stanford, the University of St Andrews, KTH and the Jozef Stefan Institute as a postdoctoral researcher. Susanne Vejdemo is a PhD student in the Special Doctoral Programme in Language and Linguistics at Stockholm University. The goal of her PhD project is to try to determine what kinds of semantic content have an effect on the speed of lexical change, and to present a theory about the relative importance of semantically-triggered change, in contrast to such factors as psychological forces, sociocultural forces, cultural/encyclopedic forces and other linguistic forces.

Susanne Vejdemo is a PhD student in the Special Doctoral Programme in Language and Linguistics at Stockholm University. The goal of her PhD project is to try to determine what kinds of semantic content have an effect on the speed of lexical change, and to present a theory about the relative importance of semantically-triggered change, in contrast to such factors as psychological forces, sociocultural forces, cultural/encyclopedic forces and other linguistic forces.